“Poland’s struggle to regain its independence seemed part of a wider European struggle between the liberation movement and the Holy Covenant. The Poles hoped for support from France, and the centre of Polish political emigration was in Paris”, states professor Piotr Szlanta from the Warsaw University.

polishhistory: As a result of the three partitions perpetrated by Prussia, Russia and Austria, the Polish-Lithuanian state disappeared from the world map at the end of the 18th Century. In 1863, not many remembered the times of the First Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Had Poles accepted their lot?

Professor Piotr Szlanta: Obviously they had not, as evidenced by their numerous attempts to regain independence, such as the Kościuszko Uprising, the Polish Legions who fought alongside Napoleon, the birth and military efforts of the Duchy of Warsaw, the November Uprising, and the existence of conspiracy organizations in exile. This, of course, did not mean that the Polish lands were undergoing constant upheavals. The Polish nobility joined the Russian, Austrian and Prussian state services, i.e. the army and administration. They had to earn their living, after all. On the other hand, for peasants who at the time constituted the majority of the Polish nation, and who were poorly educated and had a weak national consciousness, the most important issue was the possession of land, or the abolition of serfdom. The partitioners were thus trying to manipulate the social conflict that arose between the village and the manor.

What was it like in the Kingdom of Poland following its establishment by the Congress of Vienna in 1815?

During the Napoleonic era, Poles demonstrated how strongly they felt about the idea of their own state. This was noted by Tsar Alexander I, who, between 1814-1815, was striving to gain their sympathy. It is mainly due to his insistence that the Congress of Vienna decided to return the Kingdom of Poland to the political map of Europe. Afterwards, Poland was in a real union with Russia, with its own constitution, legal system, government, parliament and army. Its status was problematic though, as the tsar and his governor gradually encroached on the Kingdom’s independence in the years following its foundation, i.e. limiting civil rights. Nevertheless, under the Russian partition, the Polish nation enjoyed somewhat favourable conditions for development.

The November Uprising of 1830-1831 against Russia brought this situation to an end. The uprising was suppressed and followed by severe repressions. Why, despite this oppression, were there still attempts to fight back?

It seemed that at the mid-19th Century, the Polish national movement could count on allies in other countries. In this period, the Germans as well as the Italians were trying to bring about the unification and birth of their own nation-states. The Hungarians also dreamed of shaking off the Habsburg yoke, while the nations of the Balkan Peninsula aspired to free themselves from the Turkish one. Moreover, not all Russians were happy to accept tsarist despotism. Poland’s struggle to regain its independence seemed part of a wider European struggle between the liberation movement and the Holy Covenant. The Poles hoped for support from France, and the centre of Polish political emigration was in Paris. After the February Revolution in 1848, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte assumed power, first as president and later as emperor, and began proclaiming national liberation. Meanwhile, Great Britain was Russia’s rival in the international arena, as proved by the Crimean War (1853-1856).

On 22 January 1863, the uprising against tsarist Russia broke out. What were its reasons?

Before the outbreak of the uprising, a kind of moral revolution took place in the Kingdom of Poland. Poles had recovered from their depression following the November Uprising (1830-1831) and believed that the time had come to “fight for independence.” They expected, that as a result of the reforms undertaken in Russia after the defeat in the Crimean War, the Kingdom of Poland would at least regain the autonomy it had enjoyed after the failure of the November Uprising. However, the tsar was not ready for any compromise (Tsar Alexander II during his visit to Warsaw said to representatives of the Polish society: ‘No dreams, gentlemen’), and Poles were demonstrating increasing impatience. This could be easily noticed, for example, during mass services and patriotic manifestations on the streets of Warsaw. Several of them had ended in a bloodbath. As a result of this impatience, conspiracy organizations were reborn. The vastly unpopular Prince Aleksander Wielopolski was appointed the head of the Kingdom’s administration and in January 1863 issued a call for military conscription. By enlisting the most patriotic young people, he wanted to paralyze the underground activity, whose existence he was well aware of, and prevent the outbreak of an uprising.

Poles had generally been forced to enlist in the Russian army over the 30 years that had preceded the uprising. How did Aleksander Wielopolski trigger the outbreak of violence?

Earlier, Polish society had been terrorized, repressed or – after the Crimean War – been waiting for the tsar to make concessions. Successful conscription of Polish youth would prevent the independence movement from growing for many years. For this reason, conspiracy leaders operated under a time pressure. They could either begin the uprising in January 1863, counting on the mass support of the peasants and help from Western powers, or reconcile themselves to the prevailing system.

Let’s talk about the chances of the Polish patriots. Were the conspirators prepared for the uprising?

Of course they weren’t. It was not a good idea to undertake a fight in the middle of winter, but the enemy was ready. The insurgents lacked almost everything, especially weapons and ammunition. Despite the decree granting the land to the peasants, the insurgents failed to convince them to participate in the uprising en masse. They also counted on the help of opponents of the tsar, who could be found within the ranks of the Russian army. However, their help turned out to be quite limited in scope.

What were the aims of the commanders? Who were they? What was their message?

The main goal was to gain independence. The chief commanders operating underground had significantly different ideas about the tactics that needed to be undertaken. Radicals, called ‘Reds’, saw greater chances of success in activating peasants who were promised broad social reforms. Only they could successfully oppose the huge mass of Russian troops. In turn, the more conservative wing , the’Whites’, were afraid of too far-reaching changes in the socio-economic structure of the Polish country, that might, as a consequence, lead to a loss of influence and income. They, in turn, looked at the uprising as a kind of military demonstration, which would persuade France and Great Britain to engage militarily on the side of Poles.

After the November Uprising, thousands of Poles had emigrated – including patriotic representatives, often well-educated elites. Polish refugees were extremely active. Did they influence the outbreak of the uprising? In addition to their activity, did Polish conspirators take into account the international situation?

The conspiracy movement was born mainly within the Russian partition. The generation of November insurgents who had emigrated was slowly dying out. Of course, the emigrants, benefiting from contacts they had established in Paris and London salons, lobbied for the uprising and called on the Western powers to use at least intervene diplomatically. However, at the time, apart from official letters of protest, they were not ready to really help the Poles. Emperor Napoleon III accused them of always organizing uprisings at the wrong moment. Władysław Czartoryski, reporting to the insurgent authorities in Warsaw on his talks with the British, wrote that “in London they speak of us as already dead”.

During the uprising over a thousand battles took place. What can we say about the nature of the fighting?

The fights between the two forces were mainly of a partisan nature. However, there were some larger battles involving greater numbers of insurgents (2-3,000), i.e. the battles of Węgrów, Małogoszcz, Grochowiska, Kiejdans and Opatów. Nevertheless, the insurgents failed to take the strategic initiative or to occupy any of the cities of the Kingdom of Poland or Lithuania for any significant time. They had to hide in the woods in order to avoid being surrounded and killed by Russian troops. In fact, the Polish fighters were often pushed to the borders with Prussia or Austria, often crossing over and laying down their arms. Overall, the Russians significantly outnumbered the Poles and were better equipped from the very beginning. The transport of troops and supplies was facilitated by the railway connecting Warsaw with St. Petersburg, which was opened in 1862. In the summer of 1863, there was a maximum of 20,000 insurgents on the battlefield, however, by January 1863 there were over 90,000 Russian soldiers in the Polish Kingdom. In 1864, half a million tsarist soldiers were sent to garrison in the western parts of Russia, where the uprising was dying.

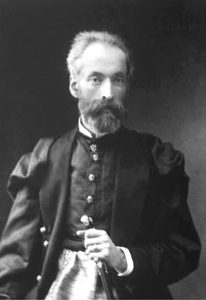

Juliusz Kossak (public domain)

The 19th Century is a period of profound social and political change in Europe. Insurgent slogans were a part of this, connecting people of different class, origin and religion. What made them so attached to the issue of Poland’s freedom?

It is worth paying attention to the role of women. They brought up generations of young Poles in a spirit of attachment to their lost homeland and nurtured their readiness to fight for it. Some of these women fought in the uprising, armed. Others used to make uniforms, treat and look after the wounded, carry reports or hide those who were being hunted. Even Russian investigators noticed this. One of them reported that although there were two parties in Poland: White and Red, all the women were Red.

What did the international background of the uprising look like? Without support from abroad, did the insurgents have any chance of defeating a Russian army that outnumbered them and was far better equipped? Let’s put it another way – was victory at all possible?

I believe that when faced with the resources of tsarist Russia, the insurgents could not win without the help of the Western powers. Meanwhile, as for the other partitioning powers, Prussia cooperated with the Russians in suppressing the Polish rebellion, while the Austrians in Galicia turned a blind eye to Polish nationalist activity, i.e. collecting money and weapons or forming insurgent troops that were soon to be transferred to the Russian partition.

Various countries around the world expressed their support and Polish insurgents received assistance in various forms. A special prayer for the Polish nation was composed, for example, by Pope Pius IX.

Yet the expression of support – as you can see – did little to help. Support was also expressed by French and British workers, which gave rise to the First International.

The insurgents were extraordinary organisers, which is often forgotten in Poland. They managed to create extensive structures of an underground state, which – in the case of victory – could be transferred 1:1 to an independent state.

A complete state “machine” was indeed established underground. The National Government passed laws and collected taxes. There was also an insurgent justice system. Many lower-level government officials also worked for the underground state. Due to the conspiracy, the National Government’s decisions were stamped with an official seal, which made them identifiable to others, as members of the Government could not reveal their identity.

What role did the uprising dictators, Marian Langiewicz and Romuald Traugutt, play?

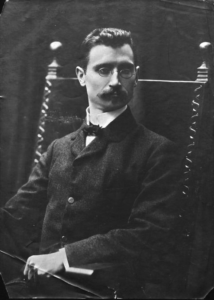

Marian Langiewicz turned out to be a good commander, although he was forced to leave the Kingdom of Poland. He was the uprising’s dictator for only eight days. The fact that the uprising was prolonged until the summer of 1864 was Traugutt’s main accomplishment. He hoped that the crisis around Schleswig-Holstein and the war between Denmark and the German Union that broke out in February 1864 would help make the Polish cause heard in the international arena. This was in vain though, and Traugutt was arrested two months later and hung after trial in August 1864.

Can we say that the tsarist decree of March 1864 concerning the abolition of serfdom and granting land to peasants could be considered a landmark event for the final defeat of the uprising?

In my opinion, we can. From that moment it was difficult to count on the mass participation of peasants in the uprising. Their most important postulate had been fulfilled by the tsarist authorities, who had the means to implement their decision. In addition, the conditions of the abolition of serfdom of the peasants were very favorable for them but at the same time they were against the interests of the patriotic nobility. Some of them were unable to adapt to the new capitalist conditions of farming and were declassified.

So what were the consequences of the fall of the uprising for Polish society and the status of the Kingdom of Poland?

Thousands of Poles were sentenced to death for participating in the uprising, others received heavy prison terms or were exiled deep within Russia. Emergency rule was declared, granting the General Governors quite broad powers, and lasted for many years. As a result of the defeat of the uprising, the Russians enforced a Russification policy in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the following years, the Kingdom of Poland was unified with the rest of Russia, liquidating its separate political institutions, and even its name. The term Kingdom of Poland was replaced by a name offensive to Poles, Przywiślański Kraj (The Country by the Vistula River). Numerous Russian officials, teachers and military men arrived. The Polish language was eliminated from administration, education and the judiciary. The Catholic Church, considered to be a refuge of Polishness, was persecuted. Prisoners awaited imprisonment or exile to distant Siberia, or emigration. To “russify” the appearance of cities, splendid Orthodox churches were built with state money.

Post-uprising repression turned out to be very severe and exerted a great influence not only on the political situation of Poles, but also on Polish culture and traditions.

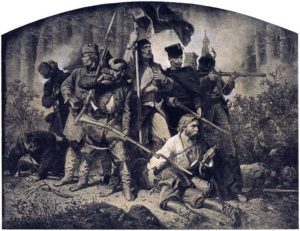

The mood at the time was probably best symbolized by Artur Grottger’s artworks depicting dramatic scenes from the January Uprising. The uprising itself is widely recognized as a symbolic end to the romantic era in the history of Polish culture. After 1864, Polish society was again effectively terrorized and oppressed by Russia. Social activists focused on organic work and grassroots social reform via promoting education, hygiene, and economic activity among the lower classes, to strengthen and enrich Polish society. These also worked to combat superstition. The political landscape of the Russian partition for over twenty years was characterised by stagnation and depression. It wasn’t until the 1880s that political parties began to form – including socialist ones – aiming for national and social liberation.

How did the January Uprising influence the next generations of Poles fighting for the independence of the country?

It was considered the next stage in the fight for independence, a change in the relay race of generations fighting for freedom. In Galicia and to a lesser extent in the Prussian partition, the memory of the uprising was cultivated and its subsequent anniversaries were celebrated. There were mass services, exhibitions of memorabilia, and books were published. Veterans of the uprising, wearing special clothes modeled on uniforms, enjoyed great social respect in the Austrian partition.

In 1918, the dream of generations of patriots fighting for independence came true. Poland regained freedom. Dramatic photographs of the interwar period show the last veterans of the uprising, who were greatly appreciated and respected in free Poland.

Józef Piłsudski, one of the fathers of independence, had a lot of respect for them. When preparing the fight for freedom, he studied the course of the January Uprising in order to learn its lessons for the future. He even wrote a book about it. His legionaries considered themselves continuators of the insurgents’ work. For the generation already raised in free Poland, the January insurgents, as well as fighters for independence, were a model of self-sacrifice for the country and freedom. Shortly after 1939, the generation of the Second Polish Republic had to pass the exam.

Interviewer: Piotr Bejrowski

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin