After 1976, Hungarian dissidents paid special attention to the situation in Poland and how it developed. Many of them even visited Poland to see it with their own eyes. The idea of “Solidarity” found fertile soil in Hungary, where, under Polish influence, the democratic opposition solidified significantly and expanded its reach.

by Gábor Danyi

The establishment of the Workers’ Defense Committee and later Solidarity inspired the activities of opposition groups throughout Central Europe to an unusual extent, giving them patterns of action. The idea of Solidarity and its program quickly crossed the Polish border and spread both in Czechoslovakia and in Hungary.

The ideas and proposals of the Polish opposition most likely first made their way to Hungary through specific texts. In 1976, two philosophers who had been on the authorities’ blacklist since the beginning of the decade – György Bence and János Kis – obtained access to the Workers’ Defense Committee’s texts through the emigration milieu, familiarizing themselves with such articles as Adam Michnik’s New Evolution or Jacek Kuroń’s Thoughts On Action Program. What is more, they prepared and made available to Hungarian readers a set of Polish underground texts and documents. It is no coincidence that at that time many of the Hungarian intellectuals (including János Kis) began to learn Polish.

In the second half of the 1970s, Hungarian dissidents managed to establish their first personal contacts with members of the Polish opposition. In 1977-1981, many of the Hungarian intelligentsia – sociologists, economists, philosophers – came to Poland to experience for themselves the phenomenon of “opposition in a socialist country”. In addition to the aforementioned György Bence and János Kis, writer Miklós Haraszti was one of the first travelers. Miklós Haraszti himself had experienced the repression of the system a few years earlier in 1973, when he wrote Darabbér [A Worker in a Worker’s State], a book about the difficult situation of ordinary workers for which he was brought to court and sentenced to suspended imprisonment for 8 months. In order to initiate contacts with the Polish opposition Haraszti twice – in 1977 and 1980 – went to Poland, where he met, among others, with Michnik, Kuroń, and Jan Lityński. Thanks to these contacts, he became the honorary editor of the Krytyka independent quarterly, founded in 1978, and published underground in Warsaw.

Architect and stage designer László Rajk, the son of a communist activist and minister executed in 1949 during the Stalinist purges, also came to Poland. However, he came here for a very specific purpose: Bence and Kis decided that he should have the unique opportunity to master printing techniques in Poland, without which there would be no question of launching any publishing initiative independent of the state. Rajk’s expedition was as full of adventures as a crime novel. In order to confirm his identity as the “Hungarian opposition delegate”, he took with him half a ten-note Hungarian forint banknote that had been previously halved by Bence and Michnik. The scraps of paper shown during the meeting fit together perfectly, and Rajk proved that he was not a security agent.

The organizer of the Budapest Flying University, Sándor Szilágyi, who had spent just a few days in Gdańsk in August 1980, would witness the establishment of the legal “Solidarity”. During the period of legal Solidarity in the early summer of 1981, sociologist Gábor Demszky set off for Poland with a camera, tape recorder, and several addresses in his pocket – without mentioning a word about his plans to anybody – in order to learn about the activities of the independent publishing houses.

The above list of names is by no means complete. People returning to Hungary usually shared their experience only within the framework of seminars of the flying university in unofficial publications, or through personal contacts. This, however, was enough for the idea of “Solidarity” to spread quickly in Hungary’s intellectual milieu.

The secret police in both countries were vigilantly and increasingly watching the intensifying exchanges through the Polish-Hungarian opposition network. They collaborated on torpedoing them, fearing an ‘internationalization’ of Solidarity. A good example of such cooperation was the coordinated repression of the sociologist Bálint Magyar, who was first expelled from Poland in January 1981 (while he was on an official delegation there!), and then dismissed from his position in Hungary. The “Magyar case” was meant to be both an example and a warning to other dissidents.

However, they continued to travel, and thanks to these travels, the programs, strategies, forms and methods of the Polish opposition became increasingly known in Hungary, primarily among dissidents who began to imitate the pattern of overt opposition activity under the so-called “democratic opposition”. The effects were spectacular in many ways.

First, unofficial institutions appeared in Hungary that operated in parallel to state ones. The Flying University (its meetings took place on Mondays in private apartments) had been operating since 1978, but in the early 1980s it significantly expanded its circle of participants. At these seminars, an increasing number of students could acquire otherwise inaccessible knowledge, including about the situation in Poland, the history of communist parties, the revolution of 1956 and the situation of Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries. In 1979, SZETA, or the Poor Aid Fund, and other independent organizations began to operate, including MUKI (the Jobseekers’ Center) and KUKI (a center for those without work), which supported those who were unemployed for political reasons.

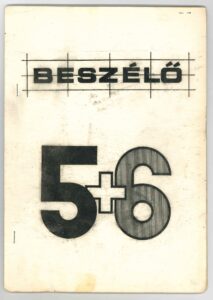

There were also significant changes in the underground circulation of publications. In 1981, a “samizdat boutique” was opened in Budapest, in László Rajk’s apartment, where everyone could buy various independent publications. Shortly after its opening, Beszélő began to appear – the first samizdat magazine produced in large quantities with the use of a duplicating machine. Among the editors were, among others, the initiators of contact with Poland: János Kis and Miklós Haraszti. By the time of the transformation, the editors of Beszélő managed to publish as many as 27 issues of the magazine, which became the most important Hungarian independent title of the 1980s. In turn, after returning from Poland, Gábor Demszky founded the Independent Publishing House AB, which succeeded in publishing about 80 books up until 1989.

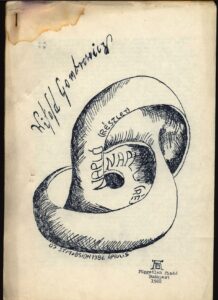

Polish influences were also evident in the selection of issues discussed within the flying university or in underground publications. Most of publications circulated in the underground in the early 1980s were translations of contemporary unofficial Polish journalism and literature works. In Hungary, Michnik’s articles on opposition programs, Jadwiga Staniszkis’s book on self-limiting revolution, as well as many political analysis and reflections, the script of the documentary film Workers ‘80, and excerpts from Gombrowicz’s Diaries were published. At the flying university seminars, the audience regularly listened to lectures on the situation in Poland.

However, the influence of the Polish opposition was not limited only to issues or creating institutions parallel to the state. Patterns of everyday life were equally important: Hungarian oppositionists learned about openness and legalism, and next to that – underground techniques that focused on creating the basic tool of independent printing, the so-called “frame” [ramka].

One of the most effective weapons of Polish dissidents was being open, i.e. referring to public opinion. The pressure of public opinion often protected them from state repression. This strategy was also adopted in Hungary. “We learned from Poles, for example, that the opposition movement is about acting openly, and that the public is a defense,” recalled Ferenc Kőszeg, a democratic opposition activist. Rajk’s samizdat boutique operated openly and publicly, everyone could find the names and addresses of the editors in the Beszélő magazine. Independent magazines regularly reported on events related to the activities of the opposition: inspections, criminal proceedings against dissidents, and fines they were charged with. The news did not only appear in the Hungarian press. It also reached Western media, primarily Radio Free Europe. This was of great importance because in Hungary – a country dependent on Western credit – the Western media pressure was on the state institutions which were supposed to limit the repression of dissidents.

One more principle originated from Poland – that opposition activity should be divided into the explicit and the hidden, namely, the underground. This way of functioning was deeply logical: it is impossible to appeal to public opinion by conducting opposition activities in the underground. On the other hand, in a situation where prominent and well-known oppositionists were to some extent defended by public opinion, it was necessary to protect those who carried out the necessary activities – from printing samizdat up to its distribution – in the background. The principle passed on to Hungarian dissidents was effectively applied in practice. In the case of all the above-mentioned initiatives – the “boutique”, the Beszélő magazine, or the Independent Publishing House AB, the group of editors operating openly with their real names and addresses, was clearly separated from the printing and conspiracy distribution network.

Hungarian dissidents often used very specific forms of instruction. It would suffice to remember Gábor Demszky whose words may serve as an example: “The technique of disappearing was explained to me in detail by my Polish friends. The main thing is to sit in one place and have all the necessary stuff in the apartment. In this way, you only need to escape once from those who follow you.”

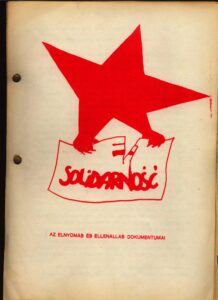

The above-mentioned “frame” also belonged to techniques originating from Poles. Poles showed this form of alternative printing to László Rajk and Gábor Demszky – (the former, thanks to his profession and experience, had already known the screen printing technique). Within a few months, suitable and widely available materials and ingredients were found in Hungary. It is significant that the first publication issued by means of a “frame” in the first weeks of 1982 were Documents of Oppression and Resistance, in which Hungarian readers were presented with Polish experiences after the imposition of martial law. The technique of the “frame” was quickly adopted in Hungary – and not only there: in time it even reached the activists of the Hungarian minority living in Romania.

Proportions of various action strategies – openness, legalism and conspiring – changed over time, adapting to the current situation. If the repression increased, dissidents responded with conspiring, if it weakened, dissidents were more open. The concept, action program and everyday strategies of “Solidarity”, despite the efforts of state authorities, administrative repression and security services, defined the forms and methods of the Hungarian democratic opposition in the 1980s. Or, repeating after Ferenc Kőszeg, Hungarian oppositionists “emerged from Polish inspiration”.

The article is based on research presented in: Gábor Danyi, “Harisnya, ablakkeret és szabad gondolat. A lengyel ellenzék szerepe az 1980-as évekbeli magyar második nyilvánosság kialakulásában”, “Múltunk” 2019/4, pp. 92-127.

Author: Gábor Danyi

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin

Additional literature:

Gábor Danyi: “Butik samizdatowy nad Dunajem”, “Pamięć.pl” 2015/7-8, pp. 60-64.

“Wracanie wolności”, ed. Gábor Danyi, “Karta” 90/2017, pp. 106-133.