He was compared to Moses taking his people out of captivity. He commanded the Polish armed forces during the most renowned attack they mounted and after the war he was supposed to return to Poland on a white horse. He was wounded on seven occasions. Deprived of Polish citizenship by communists, he became one of the key figures of Polish émigré circles. General Władysław Anders passed away 50 years ago (on 12 May 1970), almost exactly on the anniversary of the decisive strike in the Battle of Monte Cassino.

by Łukasz Starowieyski

It was a summer day marking the anniversary of another great battle when Władysław Anders spoke on the hill of Monte Cassino. The festivities of the 25th anniversary of the conquest of the fortress had been moved from May to 15 August 1969 due to General’s poor health. He reached the hill in a Jeep. As it turned out, it was one of his latest public addresses.

‘The western powers have handed Poland in to Russia… No-one is able to foresee for how long Poland will continue to suffer under a foreign regime whose might is based exclusively on Soviet bayonets. Yet we are certain that the blood bled will not be useless. Today, we want to communicate to the Polish youth the last will of our Companions lying here at Monte Cassino. Remember that what they wanted was to fight for Poland’s freedom and independence.’

Less than a year later, General Anders was buried among his soldiers at the cemetery next to the monastery founded by St Benedict.

End of wartime emigration

His death came suddenly although the over-seventy-year-old general’s health had been deteriorating for several years and he experienced cardiac and respiratory issues. However, he had attended a reception just a day before and made arrangements to play bridge the following day.

‘That evening, General talked to me frequently, we liked each other,’ said the reception hostess Irena Delmar-Czarnecka in an interview for Tygodnik Powszechny. At one point, he asked her for a cigarette saying ‘I have promised my wife and my doctor to quit smoking. I stick to the plan, but it is such a beautiful evening… And one sometimes does stupid things.’ Before bringing him a cigarette, the hostess had asked the general’s doctor, also present at her party, for approval. Anders puffed twice and said ‘You know, I somehow don’t like it but maybe it is a good thing.’ At the end of the reception, around midnight, he arranged with Kamil Czarnecki to play bridge the following day at eight in the evening. He never made it for the game, having died at 3 o’clock that night.

‘That death marked the end of wartime emigration, its “last chapter”, albeit different than the one General thought and dreamt about while writing his book. (…) A historical figure has left us,’ Jerzy Giedroyć wrote in Kultura published in Paris.

Before General was laid to rest at Monte Cassino, London had bid farewell to him first. According to Dziennik Polski published there, the requiem at St Andrew Bobola’s Church attracted as many as eight thousand Poles. Two days later, a service was also held at Westminster Cathedral. ‘The name of the late General Anders is forever connected with the Battle of Monte Cassino; no-one will be ever able to erase it from Polish hearts and the nation’s history,’ said Bishop Władysław Rubin during the sermon.

The leader of the Catholic community of England and Wales Cardinal John Heenan added that General Anders had become a symbol of a hero spurned, even in his own country, and that the Polish authorities were going to repent one day for the sin of treating Poland’s noble son that way. He also said that the entire Polish nation was a symbol in itself and lived on the hope of true freedom to which General Anders had devoted his life.

Yet not everybody was sad about General’s passing. Poland’s later president-in-exile Edward Raczyński minced no words about it when speaking a few days later during his funeral. Communists servile towards Moscow noted with irony that Anders would have liked to enter Warsaw on a white horse. Indeed, the population of the capital would have gone crazy, had that dream come true.

Scarce infromation and a smear campaign

The news about General’s death reached the entire western world and the most important European papers wrote about Anders. In Poland, however, the news was not given any special emphasis. ‘In the Warsaw press, I have found an identical note of a few lines, squeezed in between other pieces of news, lest it catch the reader’s eye making the impression something important happened. Yet on that day all my acquaintances would start the conversation with just that brief note,’ reported Benedykt Heydenkortn, the editor of a Polish émigré daily from Canada staying in Poland at that time.

A larger article was published in Życie Warszawy. ‘No-one would say he was a coward, yet it would be very difficult to talk about any impeccable features of his. (…) Anders was wrong a number of times, but most painfully in Italy in the summer of 1945, when in one of his last addresses to his soldiers he announced that he would enter Warsaw on a white horse accompanied by the sound of the bells of St John’s.’ This one arrogant statement is possibly the best illustration of his personality as well as the correctness of his political predictions.

‘That is how General Władysław Anders looks,’ is what was written slightly later in Żołnierz Wolności, ‘a man whom Free Europe and other centres of diversion are currently trying to portray as a national hero, a patriot without a flaw, a great Pole. A strange hero, indeed, who did no good for his country while doing a lot of bad due to his blindness, limitations and hatred of socialism. Gone into nothingness is a man alien to the nation, just as alien to the nation were the objectives he was pursuing.’

In yet another article, the daily treated Anders even worse: ‘It should be treated as plain obscene (…) that attempts are made to present his late person as some kind of patriotic symbol and to ascribe an almost heroic importance to him. (…) In short – his long-lasting malevolent activities directed against People’s Poland are supposed to ensure him a lasting place in national history.’

Communists considered Anders one of their arch enemies. Not without a reason, yet possibly not since the very beginning.

Number one enemy

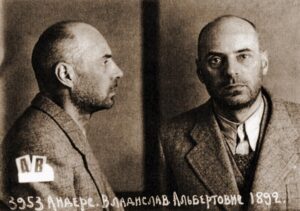

Captured by the Red Army in 1939, Anders was placed in Lubyanka prison unlike thousands of other Polish officers sent to the camps in Kozelsk or Ostashkov. He was to have been encouraged to join the Soviet army but also brutally interrogated and tortured. Released under the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement, he began to organise Polish troops in the USSR in the second half of 1941. In March 1942, against what the government-in-exile was right, he decided to evacuate his army as well as the civilian population. By the end of that year, more than 115,000 persons (78,000 soldiers and 37,000 civilians) left the Soviet Union. They first went to Iran, and later to Iraq and Palestine. In 1944, the Polish corps, already without civilians, was moved to Italy.

The soldiers and civilians who had left the USSR with Anders often referred to him as Moses. Communist propaganda treated their departure as a cowardly escape and desertion from the battlefield.

In May 1944, the 2nd Corps led by him took control of the hill of Monte Cassino, and then liberated such cities as Ancona and Bologna. Yet it was some other fight that mattered most. After the Yalta arrangements, Anders wanted first and foremost to keep the number of soldiers in his corps unchanged. He predicted another war would break, that time around between the Allies. Then, a corps of over 100,000 soldiers could become of great significance.

That is why, having received an order to reduce his army down to 80,000, he obeyed but only officially. In actual fact, he did not released anyone, only lowering the pay and food rations as he was planning to expand his army. ‘This afternoon, Anders again came to see me (…) He says there are at least one million Poles in Western Europe which he can (and wishes to) get hold of to swell his forces. He wishes to take part in the occupation of Germany and then has wild hopes of fighting his way home to Poland through the Russians! A pretty desperate problem the Polish Army is going to present us with,’ recalled British Field Marshal Alan Brooke. The Polish corps was finally disbanded in 1946.

He did not hide his hostility towards the Soviets. ‘He told me, laughing, that if his corps got in between a German and Russian army, they would have difficulty in deciding which they wanted to fight the most,’ recalled the American General George Patton.

No wonder it was he that the Poles awaited and for the communist authorities he became one of the greatest enemies. In 1946, General Anders and 74 other high-ranking military men was stripped of Polish citizenship. ‘At Monte Cassino, the Fatherland was liberated and two years later in Warsaw my activity supposedly hurt the most vital interests of the Polish state, putting at risk its security and border integrity,’ embittered Anders wrote in his memoirs.

Communists’ printing houses began to churn out such lampoons as ‘Lord Anderson’s Career’ by none other than Jerzy Borejsza: Let everyone remember that figure of a murderer, adventurer, deserter, sell-out, traitor of his fatherland and an international spy. The notion of General’s return on a white horse was also derided. Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, back then a poet laurate of those in power, wrote a poem titled ‘The Death of an Intelligentsia Man’ in 1947, which started like this: Having a cold. Apolitical. / Pained. Nostalgic. / Mincing around. Looking inside. / He would like to. He would wish to. He could. If only. / He rubs his eyes. He looks through the window panes. / A White Horse? No, it is the snow falling.

Until his death, Anders was also one of the key figures in the émigré circles. From 1949 onwards, he was president of the National Treasury, and in 1954 became a member of the Council of Three, one of the most important bodies bringing together Polish émigrés. He was also president of the Polish Educational Society and chairman of the Polish Culture Council. In 1946, he set up a team that was to establish the Polish Literary Institute in Rome, one of the most acknowledged émigré publishing houses earning its reputation thanks to issuing such periodicals as Kultura or Zeszyty Historyczne. Anders was meeting key western figures like presidents Dwight Eisenhower or John Kennedy. However, contrary to what the communist authorities claimed, he was also pursuing such objectives as the final recognition of Poland’s western border.

Let us return to his funeral and a quotation from Edward Raczyński’s speech: ‘Each good initiative could count on his support, which was not insignificant given General’s major influence across the western world.’

Author: Łukasz Starowieyski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin