“The regime in the camp was not as tough and inhumane as in the Nazi camps. But one cannot say it was gentle.” With these words Henryk Vogt summarized his stay in the Miranda de Ebro concentration camp in the Spanish province of Burgos. Although some of the brightest Polish artists, scientist and soldiers passed through this notorious place, its history seems to be largely unknown. Let’s have a look at the camp’s reality from the perspective of its Polish prisoners.

by Dorota Choińska

The Tower of Babel in war-torn Europe

The history of the concentration camp in Miranda de Ebro began in 1937, during the Spanish Civil War. It was one of many concentration camps set up by the national government of General Francisco Franco to intern the Republican prisoners of war, both Spanish and international.

Soon after the Spanish fratricidal conflict had finished, another war broke out on the European continent. After Germany and the Soviet Union jointly subjugated Poland in September 1939, Hitler’s view turned to the West. The German army quickly defeated France in June 1940. When the French state collapsed, an avalanche of refugees headed to Spain, seeking safe haven from the Nazi persecutions. It was increasingly difficult to obtain the indispensable documents to cross the border legally. As a result, many people resorted to crossing the border in secret through the high peaks of the Pyrenees.

According to the British ambassador in Spain (1940-1944), Samuel Hoare, around 30-40 thousand refugees fled to Spain illegally during the Second World War. Although Spain was officially a neutral country, fugitives from France could not count on a benign treatment. Some of them managed to transit through the Iberian Peninsula unbothered by the police, but many were detained by the Spanish Civil Guard. On 4 July 1940, the Spanish authorities decided to use the existing settlement in Miranda de Ebro as an internment camp for the men of military age entering the country. Until its closure in 1947, a total of around 15,000 people were interned in this concentration camp. They were citizens of 67 different countries, mainly French, Canadian, British, Belgian and Polish. The Poles represented the second or the third largest national group in the camp.

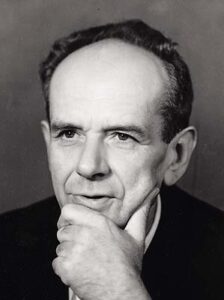

An exemplary Polish refugee – Antoni Kępiński

One of the Polish prisoners of the Miranda de Ebro concentration camp was Antoni Kępiński. He was only a humble, 18-year-old student of Medicine from Cracow when he first set foot in Spain. Soon, and partly thanks to his experience of life in the camp, he was to become a psychiatrist and philosopher of international renown.

His war-time adventures are representative of the Polish prisoners in Miranda de Ebro. In September 1939, he fled to Hungary along with the retreating Polish Army. He was interned in several concentration camps until he managed to escape to France. There, he served in the 1st Grenadier Division until the French government signed the armistice in June 1940. He soon started preparing an escape via Spain to Great Britain. His journey across the Pyrenees began in September 1940 and took 7 days. Kępiński and his companions had to endure hazardous weather conditions: snow, extreme cold, slippery slopes and fog, as well as exhaustion and terrible hunger. On 16 September 1940, they arrived at the first settlement in Spain. They must have certainly felt the refreshing breeze of freedom when they realized that they had successfully made it to the other side of the border. But the bliss did not last long. After a few days in Barcelona and Madrid, they were arrested by the Spanish police when they were heading to Portugal. They were thoroughly interrogated and, on 1 October 1940, they arrived in the infamous concentration camp in the province of Burgos.

General Franco vs. the refugees

The attitude of the Spanish government towards the refugees was a result of diplomatic pressure applied by the Allied and the Axis powers and their changing fortunes throughout WWII. General Franco had just won the Spanish Civil War and started to rule over the country with an iron fist. He fervently supported the far-right ideology represented by Nazi Germany. Moreover, he was indebted to Hitler who generously sponsored the Spanish nationalists during the Spanish conflict and substantially contributed to their victory. The German Embassy in Madrid was exploiting these circumstances and regularly interfered with the transit of refugees. Franco was nonetheless bound by the deteriorated Spanish economy. It was dependent on the supplies provided by Great Britain and other countries of the Allied block. They insisted on assuring free transit through Spain of the young, strong men willing to fight against the Nazis.

The Polish government in exile did not have much influence in this “double game”. When it came to the liberation of the Polish citizens, they could only rely on lengthy bureaucratic procedures or the British intercession. This is why many Poles detained by the Spanish police lied about their nationality. They claimed to be Canadian, British or American in order to secure a better treatment and a prompt release.

Haunted in Europe, haunted in Spain – a particular case of the Jews

The Jewish inmates in the camp shared a slightly different fate. Many Polish Jews had already moved to the Netherlands, Belgium or France during the interwar period due to economic reasons and growing anti-Semitic moods in Poland. After the Nazi invasion of these western countries, they settled down in the southern part of France. The tightening grip of racial persecutions culminated in the Winter Velodrome raid in Paris on 16-17 July 1942 when around 13,000 Jews were arrested, and the mass deportations to Germany forced them to seek refuge in Spain.

Franco’s regime was very ambiguous regarding the “Jewish question” and many Jews feared deportation straight into the hands of their oppressors. Although they could practice their religion freely once they arrived to the Miranda de Ebro concentration camp, they often preferred to keep a low profile.

After the decree from 9 February 1943, the uncertain condition of the detained Jews improved. From then on, they could claim their nationality according to the country of origin without the threat of deportation or declare as “stateless” if they did not want to return there. In this case, their liberation was organized by the Red Cross or other international organizations, such as the American Relief Organization lead by David Blickenstaff or the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) represented by Dr. Samuel Sequerra.

According to the newest European fashion – conditions in the camp

Although the prisoners of Miranda de Ebro would not compare it to a Nazi Konzentrationslager, it was actually inspired by a pre-war Nazi-German camp model. Paul Winzer, a member of the Gestapo and the SS, participated in its design.

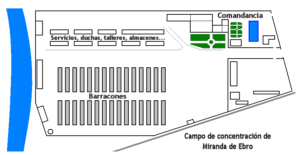

One could then notice certain similarities to the Nazi concentration camps, starting with an intimidating inscription on the entry gate: “Todo por la patria” (“Anything for the Fatherland”). The sanitary conditions were also somewhat comparable. There was never enough water in the camp even though it was situated by the Bayas river. The stream was actually used as a natural sewage system, with a sort of a scaffolding elevated over it serving as an open-air latrine. There was only one, moderately efficient well for up to several thousand men housed in around twenty unheated, dirty barracks swamped with bedbugs and lice.

The diet in the camp was extremely monotonous, consisting of badly cooked and stale ingredients. The servings were hopelessly insufficient and constant malnutrition resulted in serious health problems. Combined with the overpopulation of the camp, deplorable sanitary conditions and a lack of efficient medical care, it lead to the spread of severe infectious diseases. The prisoners in Miranda fell prey to a typhus epidemic at least three times.

The behavior of the Spanish guards and policemen was equally heinous. They treated the refugees like mere criminals and transported them to Miranda de Ebro in handcuffs. They were required to show unconditional discipline and obedience towards the camp authorities. The slightest defiance was punished with beating and solitary confinement. And since many of the Spanish guards showed sadistic tendencies, one did not need to do much to earn it. Antoni Kępiński was beaten up several times during his two-and-a-half-year stay in the camp: once for a reason as petty as leaning out of the queue to the meal.

Daily life in Miranda de Ebro

Yet another circumstance negatively affecting the inmates’ mood was the monotony of everyday life in the camp. Each activity was preceded by a sound of a trumpet: a reveille, a morning toilet, cleaning up, even the first dip of the ladle in a caldron when meals were distributed. There were roll-calls twice a day in the camp’s assembly ground. The solemn raising of the Spanish flag was accompanied by the anthem of Falange, Marcha Triunfal del Requeté, and the Spanish anthem Marcha Real. The prisoners were forced to give a fascist salute. It additionally infuriated and discouraged the refugees who had fled the atrocities of a regime that this same gesture represented. The gatherings sometimes took so long that the prisoners passed out due to exhaustion.

The long days in the camp were mainly filled with longing for home. The Polish prisoners were deeply apprehensive about their families and friends left in Nazi-occupied Poland. The letters written by Antoni Kępiński to his parents in Cracow during his stay in the camp are a testimony to the anxieties hunting the refugees in Miranda. On 19 December 1940, he wrote to his parents: “My biggest dream is to come back to You and never ever leave you again. […] Only now have I fully understood what home is.” On 14 August 1941, he shared the daunting feeling of isolation: “The news from the broad world […] does reach us here, but we are living outside of these events, as if on an island”. Moreover, like many young men forced to waste their combat potential during the idle stay in the Spanish camp, he was consumed with guilt: “I feel ashamed because I should be the one who suffers more and meanwhile, I do too well. Although it is unintentional, it is a burning remorse and I feel sorry” (2 April 1942).

Holidays were a rare break from the upsetting routine. The Spanish national holidays, such as Victory Day on 1 April or the name day of José Antonio Primo de Rivera on 20 March, were celebrated in the camp. On such occasions, the prisoners were served several different dishes instead of just one bowl of thin soup and a piece of stale fish. But the dearest occasion to the refugee’s heart was Christmas. On 24 December 1940 the Polish consul and priests came to Miranda from Madrid. They brought gifts (mainly food and snacks), celebrated a mass and organized a festive supper. The Polish inmates could enjoy the Christmas tree and typical dishes: fish, “bigos” (cabbage stew) and more. They sang Christmas carols, recited poems, performed a nativity play and exchanged wishes for a quick return home.

Fighting the apathy

The harsh conditions in the camp, unfair treatment and prolonged waiting for liberation sapped the refugee’s morale. To prevent the creeping depression, the Polish prisoners engaged in various cultural and sports activities. They organized foreign language courses and scientific lectures. They published a camp magazine and even offered a driving course – without the practical part, of course.

The greatest achievement of the Polish educational efforts in the camp was launching the middle school and high school courses along with a trading course. This “Miranda de Ebro University” boasted a brilliant team of professors: a physicist who later worked on the Apollo human spaceflight programme, Piotr Bielkowicz, poet Wacław Iwaniuk, Wisła Kraków footballer Jan Natanek, engineer Zdzisław Zakrzewski, and others. Diplomas obtained after completing these courses were later respected by the English schools.

“To break free from the apathy of body and soul”, as one of the Miranda prisoners Włodzimierz Dulniak put it, every Polish inmate was obliged to participate in everyday gymnastics. In spring 1942, with the Spanish authorities’ permission, the Polish Sports Federation in Miranda de Ebro was brought to life. It included four clubs: “Krakus”, “Kresy”, “Wisła” and “Smok”. The first president of the club was Bolesław A. Wysocki, who received a special diploma for community service in the camp from his Polish comrades. Prisoners from other nations also took to the idea. They started setting up their own federations and organized the international games in Miranda de Ebro.

Prison break – Miranda edition

Another, although very risky, way to fight the growing apathy was to plan an escape. The camp was surrounded by a wall 2-meter tall with barbed wire and guards’ booths were placed every 50 meters around it, which made breaking out no easy feat. This compelled the Polish prisoners of Miranda de Ebro to show a great deal of resourcefulness. They excavated an underground passage leading from the little chapel constructed in the middle of the assembly ground to the exterior of the camp. Once, taking advantage of an exhilarating boxing match organized by the prisoners, a Polish inmate, Banaś, who was in charge of taking the rubbish out that day, managed to take Lieutenant Rzepka, hidden in a sack, out of the camp. Lt. Rzepka remained hidden in the sack until night fell, and then cut his way out and successfully escaped. Yet another way to leave Miranda was faking illness. Lt. Zawadzki pretended to suffer from epilepsy in such a convincing manner that the camp authorities finally let him go.

Unfortunately, the majority of the escape attempts did not have a happy ending. One of those sorrowful cases reverberated particularly strongly not only around the camp, but also across Madrid’s international diplomatic community. On 4 September 1941, Lt. Stanislaw Kowalski, along with Lt. Franciszek Ciepliński and SR Jan Rudnik intended to flee. Although everything was carefully planned and the Spanish guards bribed, the escape spot they chose was under careful surveillance. While they were running away, Lt. Kowalski was shot in the leg and eventually fell. The guards, instead of calling the doctor, approached the wounded man and shot him twice in the chest and once in his head, killing him on the spot. The Polish and British ambassadors intervened, but the only result was that Spanish Lt. Saraguza, who had headed the chase, was transferred to a different concentration camp.

Worsening conditions and a hunger strike

The situation in Miranda de Ebro was aggravated significantly when the German Army occupied the whole territory of France in November 1942. An unprecedented number of refugees flooded Spain, contributing to extreme overpopulation of the camp. By December 1942, there were around 3500 prisoners residing in installations designed for roughly 1200 men.

The Polish prisoners, among whom many had already spent over two years in the camp, decided to take the matter in their own hands. On 6 January 1943, around 700 Polish inmates refused to eat their midday meal and announced a hunger strike. They demanded the Spanish authorities improve conditions in the camp and liberate the detainees. Almost all prisoners of the other nationalities quickly joined the rebellion. To spread the word about the strike outside the camp, the refugees were launching balloons made of condoms filled with gas, by night, with a note about the protest attached to it. This is how the news arrived at the British Embassy. It caused a great international scandal which forced Spanish authorities to gradually release the international prisoners. The hunger strike was officially finished on 13 January and three days later the first group of 400 refugees (among them 100 Poles) was allowed to leave the camp.

Antoni Kępiński departed from Miranda de Ebro on 20 March 1943, along with one of the last groups of the liberated prisoners. Like the majority of them, he was transported to Gibraltar and from there he embarked on a ship to Great Britain. Many Polish men joined the Allied Army and fought against Nazi Germany. Other Polish citizens, especially Jews, continued further on to the United States, South America or Palestine, where they could start their lives anew, far away from the terror of WWII.

Closure of the camp

Before the longest operating Spanish concentration camp in Miranda de Ebro was finally closed in 1947, it saw yet another wave of foreign refugees. This time, they were the German border guards, Nazi authorities residing in France and their collaborators. They were fleeing the Allied army gaining ground on the Western front and awaiting a hospitable welcome by the Spanish authorities. Although many key Nazi officials did receive privileged treatment, the majority of them still ended up as prisoners of Miranda de Ebro.

A new era of the camp began – but this is a completely different story.

***

Fragments of Antoni Kępiński’s letters and other quotes: Ryn, Z. J. (2005). Antoni Kępiński w Miranda de Ebro. W: Kępiński, A., Refleksje oświęcimskie (p. 218–285). Wydawnictwo Literackie, translated by Dorota Choińska.

Author: Dorota Choińska

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin