“The Sanation political movement was never uniform, it was bound by the person of Józef Piłsudski – his authority, and his will. When he was absent, differences became more pronounced. Each of the groups was striving to play a dominant role in the country, and be seen as the one most obviously and faithfully continuing Piłsudski’s politics” – says Professor Czesław Brzoza.

polishhistory: 1935 in Poland is associated with two important events – the April Constitution and the death of Marshal Józef Piłsudski. Let us begin with the first one. The April Constitution was received very unfavorably by the opposition in the Sejm. The ruling powers resorted to some legal tricks to push through the draft constitution.

Professor Czesław Brzoza: Józef Piłsudski’s influence on the history of the Second Polish Republic is indeed enormous, although perhaps, especially in the 1930s, smaller than his apologists would want it to be. Undoubtedly, however, with his personality, his will and his charisma, he had an influence on the situation in the country. It should be remembered that in 1937 the Sejm finally recognized 11 November as the official holiday of Poland regaining its independence, and did so to emphasize the importance of the day „forever associated with the great name of Józef Piłsudski, the victorious Commander-in-Chief of the Nation in the struggle for the freedom of the homeland.”

In 1935, the aim was to elaborate on the Constitution, taking into account Piłsudski’s point of view and ideas. Therefore, in line with previous practices, legal tricks were used in full knowledge that they were violating the provisions of the Constitution and the regulations of the Sejm that were in force at the time. To the protests of the opposition, Prince Janusz Radziwiłł answered that „insistence and fighting with the use of statutory provisions, which could be understood in one way or another, is funny, it is a childish game, [not] taking into account not only what is happening in Poland, but also what kind of upheaval is taking place around the world.” Considering the dire situation both globally and domestically [as emphasized by Radziwiłł], sticking to a strict legal provision seemed irrelevant.

How did the new constitution change the balance of political forces in Poland?

The constitution changed not so much the balance of political forces as much as it fundamentally changed the system of the state. The division of power [according to the principles of] Montesquieu was broken off because, according to the new basic law, the „one and indivisible power” was in the hands of the president. He was not only the head of the executive power, but he also took control of the previously independent judiciary, as well as of the Sejm and Senate, i.e. legislative power. On the other hand, the political situation was fundamentally changed by the new electoral law. This liquidated the principle of proportionality, introducing both special bodies with directed electoral lists controlled by the ruling party, and two various types of MP seats (mandatowe and niemandatowe – the first refer to those who entered from the top of the list, the latter to those who were placed on it lower down, as later seen in the Polish People’s Republic). The result of this action meant that the opposition was deprived of any possibility of winning elections.

How did public opinion react to this?

I suppose, as usual, opinions varied. For a large part of the not very politically educated society, these issues were distant, difficult to understand, and, therefore, of little interest. Besides those who were deeply committed for various reasons, supporters of the ruling power treated the situation as a fully understandable victory for their political faction. On the other hand, opposition activists emphasized, above all, the violation of the binding law and they claimed that the constitution was illegal in this regard. They adhered to this attitude at least until the outbreak of the war, when, thanks to this same constitution, the continuity of the state was saved and opposition groups assumed power.

Did the new constitution, which introduced a strong presidential power, really stabilize the political system in Poland? Or was it not so much about stabilizing and confirming his dominant position in Poland as about securing one’s own interest in the face of the Marshal’s possible death?

It seems that the goal of every political faction is to gain power, and later – strive to keep it. Of course, favorable conditions are helpful, e.g. by introducing legal solutions that help maintain power. Therefore, the so-called Brest elections (1930) were won through very unclean methods by Piłsudski’s political movement (Sanation). After gaining a majority in the Sejm and Senate, they made a thorough reconstruction of the legal order of the state. Although it was possible to unify the law and it contributed to the blurring of partition boundaries, Sanation’s political objectives did not raise any doubts – it was about strengthening its position and guaranteeing its monopoly on future power. The end of the first stage of changes was the adoption of a new constitution and related acts. The work was accelerated due to the poor health of Józef Piłsudski, and it was probably hoped that he would take the office of president. It was a kind of paradox that, in the inter-war period, two basic laws were adopted, both with Piłsudski in mind as the future president. For this reason, the legislative Sejm, with a predominance of his opponents, adopted a constitution which in principle did not give the head of state any power, while the Brest Sejm granted the president enormous power. However, both of these acts did not yield what they intended. The first, because Piłsudski took power as a result of the coup d’état and exercised it unofficially, and by way of various legal tricks, the so-called constitutional precedents, did not, in fact, have to worry about the provisions in force, and, second, because it was the last important document that he managed to sign during his lifetime.

Authoritarian rule in the 1930s was not unusual. Could you tell us briefly what the Polish political system looked like against the European background?

Democratic principles were not really popular in the interwar period. In the mid-1930s, totalitarian, dictatorial or authoritarian systems prevailed in most European countries. In our part of the continent, democratic institutions survived the longest in Czechoslovakia, but it was also probably the wealthiest country in this part of the world. It is difficult to clearly assess the Polish system at that time. Compared to our totalitarian neighbors – Germany and the USSR – we were not doing the worst. Until the end of the state, there were opposition parties as well as an associated press. There is no doubt, however, that the country had become increasingly oppressive, and the scale of repression against opponents or potential opponents was steadily increasing. This is demonstrated by, among other things, the constantly growing range of press censorship, the establishment of a prison camp in Bereza Kartuska, as well as the large number of people who were killed while suppressing the strike movement in 1936-1937.

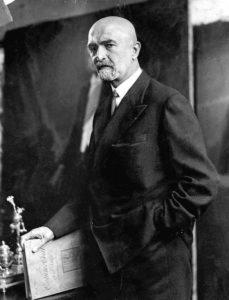

Piłsudski’s death revealed deep divisions in the ruling movement. One of the Marshal’s closest and most trusted people and long-time collaborator, Walery Sławek, was unofficially anointed by him as president. It was assumed that the current president, Ignacy Mościcki, would resign. Many accounts show that Sławek was an extremely honorable man who was able to put the public’s interest above his own ambitions. A feature quite rare among politicians.

The Sanation political movement was never uniform, it was bound by the person of Józef Piłsudski – his authority, and his will. When he was absent, differences became more pronounced. Each of the groups was striving to play a dominant role in the country, and be seen as the one most obviously and faithfully continuing Piłsudski’s politics. Walery Sławek, probably the person closest to Piłsudski, became the leader of one of the factions, the so-called colonels’ regime. This faction is known to have been eliminated from the fight for power quite quickly. Sławek had enjoyed the reputation of being an extremely honest and honorable man who knew how to give up his personal ambitions in favor of the public interest, although he seemed to have been particularly inclined to fulfill Piłsudski’s will the way he understood it. However, it is not so certain that he was honest towards his political opponents. He tried to cover up, for example, the proceedings against the Brest prisoners, and this lie had far-reaching political consequences – on the basis of his assessment, all references to the treatment of opposition leaders detained in Brest prison were subsequently erased. He did not hesitate to publicly express his belief that in the interest of the state, one sometimes needed to break an opponent’s back.

Why then did Walery Sławek not try to fight for his ideas?

Walery Sławek was an excellent executor of his commander’s orders if he received them, and at other times he at least suspected that he was acting according to Piłsudski’s will. It was worse when it came to his own decisions. At the time of Piłsudski’s death, he was one of the most influential people in Poland; he was the Prime Minister, a position conferred on him by Piłsudski, which was significant in itself, the president of the self-governing political party – the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government and the chairman of the Union of Polish Legionaries, i.e. the most numerous and the most influential veterans’ organization. In less than a year, he had lost all these advantages. But the moment President Mościcki manifested his disloyalty to Piłsudski’s will, Sławek resigned from the office of Prime Minister in protest. The Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government dissolved the organization, believing that it had already fulfilled its task, which deprived the ruling movement of any political backing, like turkeys voting for Christmas, and he agreed to be removed as the leader of the Legionnaires’ Union. His decisions can probably be seen as a form of protest against the struggle that began within the faction.

Sławek experienced one more blow – Mościcki gave the marshal’s ceremonial mace to General Edward Rydz-Śmigły. A military man, who may have been as gifted in many ways as he was, however, there were probably a dozen more distinguished officers worthy of this function. We’re talking about taking control of the army and being Piłsudski’s successor.

Granting a marshal’s ceremonial mace to Edward Rydz-Śmigły is hard to perceive as a blow to Walery Sławek. Perhaps only in the sense that it was another manifestation of disregarding the will of the late Józef Piłsudski, who said that a marshal in Poland was not needed during peacetime. I would not agree with the assessment of the new marshal, whom we most often judge from the perspective of our defeat when Poland was invaded, [a time] when no other commander would have been able to win. We forget, for example, about his fine attitude in the Polish-Bolshevik war and his efforts to modernize the army in the last years of the Second Polish Republic. I believe we would also have big trouble finding “a dozen more distinguished officers worthy of this function.” In addition, the rank of marshal did not give him anything in matters of competence. He gained actual sovereignty over the army a few hours after the death of Józef Piłsudski, when he was appointed General Inspector of the Armed Forces, i.e. an officer coordinating broadly understood”d war preparations and intended as the commander in chief in the event of war. However, his ambitions were much bigger. When he became the military successor of Józef Piłsudski, he decided that he had obtained his political rights, and thus the possibility of actually ruling the state, without any formal consequences. Indeed, he had a great influence on the functioning of the state and it had even been agreed that in 1940 he would become president.

After regaining independence, Poland had to fight for several years for the shape of its borders, as well as minimize the disadvantage which was the legacy of the partitions. This was accompanied by difficulties independent of the actions of Polish politicians, such as the economic crisis and the customs war with Germany. In the mid-thirties, many industrial investments helped the situation in the country. There was plenty of success in this field.

The Second Polish Republic was marked by a poor economic situation. After the end of the First World War, when almost all countries had shifted their economies to a peaceful track, Poland entered a period of armed conflict with its neighbors for several years. One of the consequences of this was inflation followed by an economic crisis which lasted much longer in Poland than in other countries. The second half of the 1930s was definitely a successful period. It was indeed a time of great investments, especially related to the expansion of Gdynia and the construction of the defense industry in the Central Industrial District. However, it seems that Poland’s most important achievement in the interwar period was the creation of a single internal market and the weakening of economic links with former occupiers.

The mid-thirties was also a period of high economic development of the Second Polish Republic after the international crisis, when ambitious plans for modernizing the state were being implemented. Poland had not yet been able to compete with the strongest countries, but probably the effects of this development could have been felt. Regardless, there was an increased exasperation among people of certain milieu, which led to strikes.

The improvement in the economic situation in the second half of the 1930s was evident, but this does not mean that Poland was any closer to the most developed countries. There was still a large disproportion in almost all areas. Certainly a part of society benefited from the improvement, but the number of those dissatisfied was still huge. The improvement of living conditions also did not take place automatically with the economic recovery. For these reasons, in the second half of the 1930s, there was a huge wave of industrial strikes (1936) which resulted in bloody street clashes. Equally dramatic was the great peasant strike in 1937, during which over 40 people were killed. In the following years, although there were still numerous conflicts, the situation slowly stabilized.

However, the reality was beginning to be overshadowed by the increasingly aggressive Germany, which had already been openly building international alliances. The symbol of this was the visit of Hermann Göring to Białowieża in January 1935 and an attempt to persuade Polish leaders to join the alliance against Russia. Marshal Piłsudski, then weak and sick, strongly rejected the German proposal. Why?

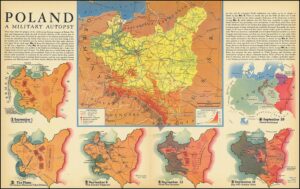

One of the cornerstones of Polish diplomatic activity during the post-war period was the so-called balance policy, also called the policy of equal distances. It assumed that Poland would strive to improve relations with its neighbors, especially the largest and most dangerous ones – Germany and the USSR, and would not sign any agreements with one of the neighbors against the other. In other words, Moscow and Berlin were to remain politically equidistant from Warsaw. This policy yielded some results. In 1932, a non-aggression pact with the USSR was concluded (then extended in 1934 for ten years) which was followed by a non-aggression pact with Germany in 1934 for ten years. It might have seemed that Poland would have been protected for some time. It was because of the principles of Polish foreign policy that Piłsudski did not want and could not accept German proposals to create a common front against Russia. I don’t know if he also anticipated that cooperation with Germany would, as a consequence, have led to Poland’s subordination to Germany.

German actions on their own territory were also dangerous. In 1935, the Reichstag adopted the infamous “Nuremberg Laws” and Heinrich Himmler became the head of Lebensborn. I am asking about it for a reason. Shortly after Hitler took power in 1933, Piłsudski signaled to France the need to organize a joint action against Germany which he assumed to have been threatening the European order. Not only were the French and British not ready for this action, they were also not particularly interested in the next war. Was it possible to stop the Third Reich in 1935?

The proposals of the so-called preventive war are not documented. There are no explicit confirmations in known archival materials. Also, Western politicians do not mention them in their memoirs, although on the other hand, if they really received such signals and downplayed them, they would have nothing to brag about and it would be better not to write about it. The British and French certainly did not want war, and they thought that peace could have been achieved by making concessions to German demands. Many of them were considered justified. After all, the Western countries did make such concessions soon after the signing of the Versailles Treaty. These countries cared first and foremost about their own interests, which is fully understandable. Their failure lies in the fact that they did not notice that such a policy did not bring results, did not consolidate peace, and only created new tensions. For Poland, for example, the position of our French ally during the Locarno conference was a bitter moment in which the Polish-French alliance was clearly weakened. The question of whether it was possible to stop Germany in 1935 is only theoretical. One can only assume that a decisive reaction from France and Great Britain would have delayed events, but were they able to fundamentally change the course of history? No one can know this for sure.

Czesław Brzoza is a historian specializing in the modern history of Poland. He is a professor at Jagiellonian University and a member of Polish Academy of Learning.

Interviewer: Piotr Abryszeński

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin